A research project has identified teacher resilience as being key to outstanding teaching and learning in schools. Professor Chris Day explains the key messages from the research for schools, teachers and heads.

It is a truism that over a lifetime, most workers, regardless of the particularity of their work context, role or status, will need at one time or another – for shorter or longer periods, or as an everyday feature of their work processes – to call upon reserves of physical, psychological or emotional energy if they are to carry out their work to the best of their ability.

Schools and classrooms, especially, are demanding of energy of these kinds, partly because not every student chooses to be there and partly because successful teaching and learning requires cognitive, social and emotional investment by both teachers and students.

Given the likely associations between resilience and teaching quality, it is all the more surprising, therefore, to find that the capacity and capability to exercise resilience in schools has been largely ignored by governments and researchers in the past who have preferred instead to focus upon problems of teacher stress, burn-out and retention.

While the final report of the Skills Tests Review Panel to the education secretary in June, commissioned by the government to review the recruitment and selection procedures, identified the need for new written tests in literacy, numeracy and reasoning, it also recommended that so-called, “personal qualities such as oral communication, empathy and resilience” should be “the responsibility of providers of training”.

Notwithstanding the difficulties of one-off testing for resilience capacity and capability, it does seem to be important to address the issue. Which parent, for example, would want their child to be taught by a teacher who was unable to do so because their capacity for commitment, their sense of resilience, had become eroded over time? Here is what one experienced teacher said: “Sometimes you think, why do I keep doing this? They are never going to learn and nobody appreciates it. I think I have less belief in my ability to be effective the longer I’m here.”

Rather than ask how we can prevent stress and mental/emotional ill-health or how we can retain teachers, the more important questions are: “How can we foster resilience and what types of training, support, work environment, culture, leadership and management practices will facilitate its development?

These questions were the subject of a recent seminar series funded by the Economic and Social Research Council and attended by teachers, heads, academics and members of national policy organisations.

Evidence presented during this series suggests that employers in general tend to underestimate the extent of psychological ill-health among their staff. Psychological ill-health, whether work-related or not, is estimated to cost UK employers approximately £25 billion a year. On average this equated to £1,000 per employee.

This figure includes sickness absence and replacement costs, but also the reduced productivity of staff who attend work but who are unwell, a phenomenon known as “presenteeism”. The Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health’s report in 2007 estimated that presenteeism accounted for at least 1.5 times as much lost working time as absenteeism.

Although precise figures for the education sector are not available, it is not unreasonable to assume that the extent of presenteeism there may be as considerable as it is for the workforce as a whole: a substantial number of teachers may be attending work while not well. Over time this suggests that they will not be able to teach at their best.

A key strand of the seminar series, therefore, was the presentation and examination from psychological, sociological and policy perspectives of national and international research knowledge of the work and lives of teachers.

Taken together, these showed that while many teachers enter the profession with a sense of vocation and with a passion to give their best to the learning and growth of their pupils, for some these become diminished with the passage of time, changing external and internal working conditions and contexts, and unanticipated personal events.

They may lose their sense of purpose and wellbeing which are so intimately connected with their positive sense of professional identity and which enable them to draw upon, deploy and manage the inherently dynamic emotionally vulnerable contexts in which they teach and in which their pupils learn.

In a 2008 survey among teachers in schools in England, for example, teachers reported the damaging impact of these symptoms on their work performance. Issues were, in rank order, excessive workload, rapid pace of change, pupil behaviour, unreasonable demands from managers, bullying by colleagues, and problems with parents.

One of the conclusions of the seminar series was that the more traditional, psychologically derived notions that resilience is “the ability to bounce back in adverse circumstances” do not lend themselves to the work of teachers.

Resilience is not a quality that is innate. Rather, it is a construct that is relative, developmental and dynamic. A range of research suggests that resilient qualities can be learned or acquired and can be achieved through providing relevant and practical protective factors, such as caring and attentive educational settings in which school and academy leaders promote positive and high expectations, positive learning environments, a strong supportive social community, and supportive peer relationships.

Without organisational support, bringing a passionate, competent and resilient self to teaching effectively every day of every week of every school term and year can be stressful not only to the body but also to the heart and soul – for the processes of teaching and learning are rarely smooth, and the results are not always predictable.

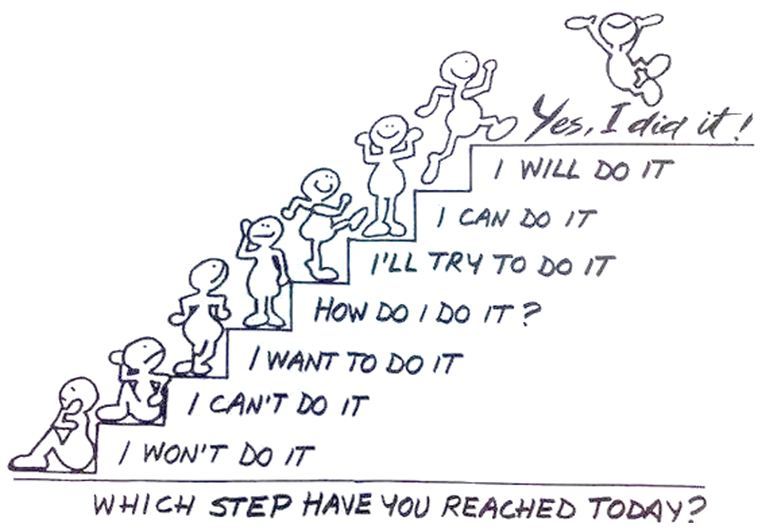

The seminar series concluded that to teach to one’s best over time requires “everyday resilience”. This is more than the ability to manage the different change scenarios which teachers experience; more than coping or surviving.

It is being able to continue to have the capacity and capability to be sufficiently resilient, to have the desire and the energy as well as the knowledge and strong moral purpose to be able to teach to their best.

The capacity to be resilient in mind and action is likely to fluctuate according to personal, workplace and policy challenges and pupil behaviour; and the ability of individuals to manage the situations in which such fluctuations occur will vary.

The process of teaching, learning and leading requires those who are engaged in them to exercise resilience on an everyday basis, to have a resolute persistence and commitment, and to be supported in these by strong core values.

It is this more positive view of teacher resilience associated with teacher quality which should, we believe, inform policies of selection, recruitment and retention. The key messages from the research seminar series are that:

- Teaching at its best is emotionally as well as intellectually demanding work and demands everyday resilience.

- Levels of work-related stress, anxiety and depression are higher within education than within many other occupational groups.

- Rather than focusing upon managing stress, a more productive approach would be to focus upon fostering and sustaining resilience.

- Resilience is more than an individual trait. It is a capacity which arises through interactions between people within organisational contexts.

- Teachers’ resilience needs to be actively nurtured through initial training and managed through the different phases of their professional lives.

- Because government has a particular responsibility in relation to teaching standards, it needs to ensure it establishes national policy environments which acknowledge the importance of resilience to high quality teaching.

- School leaders have a particular responsibility to foster and nurture teachers’ capacities and capabilities to exercise everyday resilience in order to ensure that they are able, through who they are and what they do, always to teach to their best.

Some other links:

- https://www.teachermagazine.com.au/articles/building-teacher-resilience

- https://www.weareteachers.com/keep-that-bounce-5-ways-to-nurture-your-resilience-as-a-teacher/

- https://www.brite.edu.au/

- https://www.weareteachers.com/8-ways-to-help-your-students-build-resiliency/